By: Jeffrey McNeal, EA, former Revenue Officer for the IRS

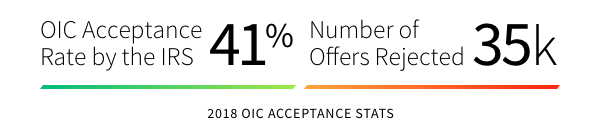

Offer in Compromise (OIC) is a program administered by the Internal Revenue Service which allows taxpayers to settle their tax debt for less than the full amount they owe— essentially allowing them a fresh start with the IRS. For tax professionals, this is a useful program to look into if you have clients who are struggling to pay their state or federal tax debt. In 2018 alone, the IRS accepted 24,000 offers, amounting to $261.3 million. They also rejected 35,000 offers. So how do you know if Offer in Compromise is right for your client? In this post, I go over tips for getting an offer accepted that I learned working as a revenue officer.

Is Offer in Compromise right for your client?

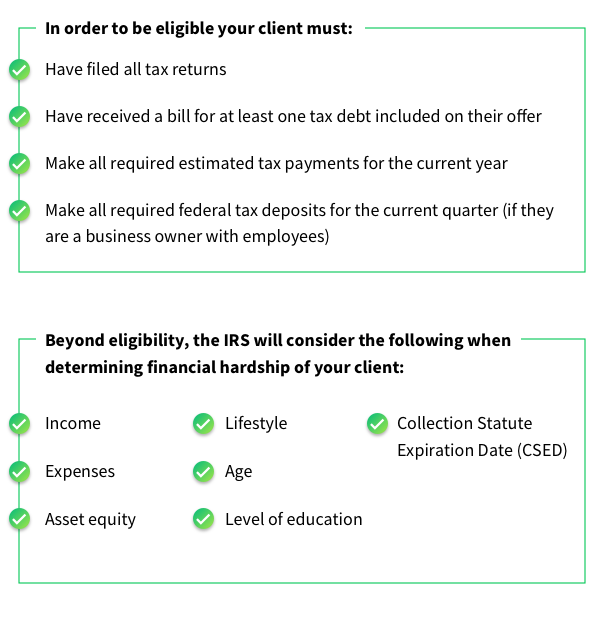

The first thing to look at when evaluating whether or not your client is a good fit for OIC is the eligibility requirements.

Keep in mind, while certain qualifications and requirements are set in stone, the offer specialist reviewing your client’s case will take into account all aspects of your client’s situation. Your client’s lifestyle will play a huge factor in whether or not the specialist recommends them for OIC. If you claim that your client can’t pay their full tax debt but they drive a brand new Range Rover and own a $2 million house, they’re likely not a good candidate for Doubt as to Collectibility Offer in Compromise.

The IRS collects most of their information about your client’s financial situation using Form 433-A (OIC), but the rest of the information is gathered through investigation. If you are able to justify your client’s abnormally high cost of living due to special circumstances, the offer specialist will take that into consideration (usually via Effective Tax Administration). Just because your client has equity in their house or vehicle doesn’t necessarily mean the IRS expects them to sell those things to pay their debt.

One final thought to keep in mind in regard to your client’s ability to pay: while an offer is being reviewed (a process that can last several months), your client’s income and assets will be under ongoing review to make sure that at no point they become able to pay their tax debt.

Applying for Offer in Compromise

In order to submit the actual OIC application, the following forms may be required (depending on your client’s situation).

This is the form required to make the offer. This form outlines the agreement between the taxpayer to pay a certain amount to cancel their outstanding debt with the IRS. This form must also be submitted to waive the application fee due to your client’s income level. If approved, this form will waive the OIC processing fee and the 20% down payment of the amount offered.

This is the form required to make the offer. This form outlines the agreement between the taxpayer to pay a certain amount to cancel their outstanding debt with the IRS. This form must also be submitted to waive the application fee due to your client’s income level. If approved, this form will waive the OIC processing fee and the 20% down payment of the amount offered.  This is the form the IRS uses to determine a taxpayer’s financial hardship. The taxpayer must list all their income, expenses, assets, and liabilities. If approved for an OIC, this form will often have to be resubmitted so the IRS can ensure that there have been no changes that would allow the taxpayer to afford to pay the tax debt. The IRS can demand that the taxpayer resubmit this form at any time to reflect their current income and expenses.

This is the form the IRS uses to determine a taxpayer’s financial hardship. The taxpayer must list all their income, expenses, assets, and liabilities. If approved for an OIC, this form will often have to be resubmitted so the IRS can ensure that there have been no changes that would allow the taxpayer to afford to pay the tax debt. The IRS can demand that the taxpayer resubmit this form at any time to reflect their current income and expenses.

This is a financial statement form similar to Form 433-A (OIC) but for businesses.

This is a financial statement form similar to Form 433-A (OIC) but for businesses.

Common OIC form mistakes to avoid

During my time as a revenue officer, I saw a lot of little mistakes on OIC forms that had big impacts on cases. Sometimes these mistakes would only cause confusion and stall the case until the mistake could be clarified. Sometimes the mistakes were enough to get the offer rejected outright. Either result is time-consuming and costly for both you and your clients. Let’s go over a few of these simple mistakes, why they matter, and the easiest way to ensure they don’t happen to you.

You probably wouldn’t expect this, but I saw a lot of bad math from tax professionals during my time at the IRS. Not because CPAs and EAs are bad at math but because perfectly filling out a Form 433 is hard. It requires juggling dozens of complex numbers and figures, not to mention all the explanations and supporting documentation that accompany the numbers. It’s no wonder the ball gets dropped sometimes.

Unfortunately, when that ball does get dropped—a quick-sale value is calculated incorrectly or an expense is included in the wrong calculation—the whole OIC process has to come to a screeching halt until the mistake is sorted out.

When I saw an empty field on a 433 or 656 (something I saw far too frequently), there was no way for me to know why the practitioner had left it blank. Was it blank because it didn’t apply to the taxpayer? Because they didn’t understand how to answer? Or was I missing information crucial to the case and the tax professional made a simple mistake? I had to know the answer before I could proceed with my recommendation on the offer. It’s a shame that something so small can hold up such an important decision, but I saw it happen often. The best way to avoid this mistake is to write either “N/A” or zero in spaces that don’t apply to the taxpayer.

This is another mistake I saw frequently: when a taxpayer’s property was worth less than they owed on it, the practitioner would often subtract that negative equity from the taxpayer’s net realizable equity (NRE). You can’t do that, helpful as it may seem to your client’s case. Any asset with negative equity should have a reported equity of zero.

The best way to fill out OIC forms

There are a couple ways you can go about making sure these kinds of mistakes don’t happen on your offers. You could hire someone to obsessively pour over every facet of an offer, recalculate every calculation and double check every form field for accuracy. You certainly don’t have time to do every offer twice.

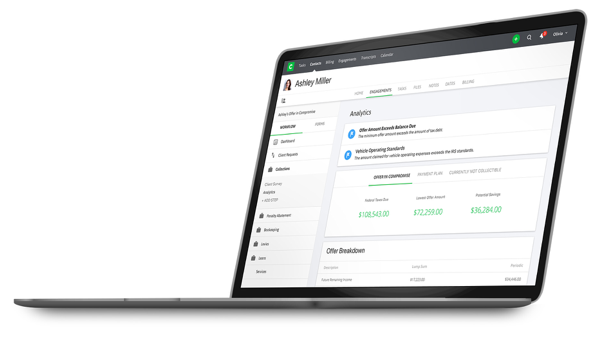

Or you can use tax resolution software to do all that for you. I can’t speak specifically to other tax resolution software, but I know Canopy solves each of the common problems I’ve outlined. When you use Canopy to prepare your client’s OIC, our software does all of the calculations for you, makes sure you don’t leave any blank fields, and helps you comply with IRS standards. Not only does that save you time, it also makes your offer more likely to be error-free. That means fewer hangups and less lost time.

Just as importantly, Canopy frees you up to worry about more important things than exactly how to comply with every nuanced IRS standard. How you spend that time—building client relationships, growing your practice, or perfecting your golf swing—is up to you.

Negotiating an Offer in Compromise

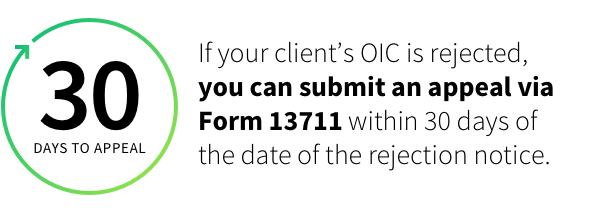

If your client’s OIC is rejected, you can submit an appeal via Form 13711 within 30 days of the date of the rejection notice. The appeal needs to address the issues raised in the OIC rejection and the taxpayer will likely have to provide additional documentation. If accepted, the appeal will allow the taxpayer the opportunity to renegotiate their rejected offer under more acceptable terms for the IRS.

To argue any of the grounds for appeal you need to be prepared to support your position with records, evidence, and procedures. An appeal is essentially a discussion between the appeals officer and you on behalf of your client, and all appeals decisions are final. If you want to win an appeal, you have to justify your client’s position by referencing your documentation and tying it together with the IRM, IRC, and court decisions correctly.

Keep in mind, ex parte communications are prohibited in the IRS which means an appeals officer cannot talk about your client’s case with the offer specialist who rejected it. Because of the unbiased nature of appeals officers, you can make your original case to them if you believe you have already included sufficient evidence. If your client’s offer was rejected based on lack of evidence, you’ll want to strengthen your case before sending it to Appeals. If you’ve already exhausted IRM and IRC references, try using case law.

Additionally, it can be effective to play to the emotional side of the argument—appeals officers are human after all—but it should be the “cherry on top” of your argument, not the basis. During my time at the IRS, I never lost an appeal hearing because I rooted my arguments in the IRM and IRC, and you can expect other IRS officers to do the same.

As I mentioned previously, the IRS rejected 35,000 offers in 2018. While the acceptance rate for offers in compromise has increased from 25% in 2010 to around 41% in 2018, there’s still a good chance your client’s offer will not be accepted. Again, the best thing to do to increase your chances of success is to be sure you can back up the foundation of your client’s case in facts and IRM references. I can’t emphasize the importance of using the IRM to support your claims enough.

Canopy is a one-stop-shop for all of your accounting firm's needs. Sign up free today to see how our full suite of services can help you.

Get Our Latest Updates and News by Subscribing.

Join our email list for offers, and industry leading articles and content.